3. German Autumn, Bitter Defeat

As we saw in our previous installments, by late summer 1977 the Red Army Faction was poised to carry out its most ambitious gambit to free its members being held captive in West German prisons. Dozens of guerillas had spent years in isolation, at times subjected to sensory deprivation torture, and yet they continued to fight for their political identity, and indeed their own sanity, through hunger strikes which mobilized support on the outside.

During the previous three years, three members of the guerilla – Ulrike Meinhof, Siegfried Hausner and Holger Meins – had died while in captivity. The radical left considered each of these deaths to be a case of murder.

As the month of August came to an end the guerilla had already carried out several attacks in 1977, killing members of the ruling class, their bodyguards and police. One of these, Jürgen Ponto, had died when he resisted being kidnapped by a RAF commando which included his own god-daughter. This had been intended to be the first of a two-pronged action to put pressure on the West German bourgeoisie to force the state to free the prisoners.

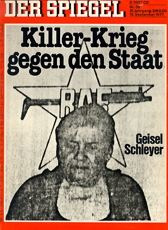

Despite their failure to take Ponto alive, the RAF decided to follow through on the second part of this plan, and so, on September 5, the “Siegfried Hausner Commando” of the RAF kidnapped Hanns-Martin Schleyer. His car and police escort were forced to stop by a baby stroller that was left out in the middle of the road, at which point they were ambushed by guerillas who killed his driver and three police officers before making their getaway.

Schleyer was the most powerful businessman in West Germany at the time. He was the president of both the Federal Association of German Industrialists and the Federal Association of German Employers. As a former Nazi SS officer, he was also a symbol of the continuity between the Third Reich and the post-war power structure.

As the guerilla would later explain:

“We hoped to confront the SPD (1) with the decision of whether to exchange these two individuals who embody the global power of FRG (2) capital in a way that few others do.

“Ponto for his international financial policy (revealing how all the German banks, especially his own Dresdner Bank, work to support reactionary regimes in developing countries and also the role of FRG financial policy as a tool to control European integration) and Schleyer for the national economic policy (the big trusts, corporatism, the FRG as an international model of social peace).

“They embodied the power within the state which the SPD must respect if it wishes to stay in power.”(3)

Despite the failure of the Ponto action, it had been felt that the plan could not be called off, that lives were at stake: “the prisoners had reached a point where we could no longer put off an action to liberate them. The prisoners were on a thirst strike and Gudrun was dying.”(4)

Within a day of Schleyer’s kidnapping, the commando demanded the release of eleven prisoners – including the RAF founders Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carle Raspe and Andreas Baader – and their transportation to a country of their choice.

Despite the fact that the prisoners offered assurances that they would not return to West Germany or participate in future armed actions if exiled, on September 6 the state released a statement indicating that they would not release the prisoners under any circumstances.

On the same day, a total communication ban was instituted against all political prisoners. The so-called Kontaktsperre law, which had been rushed through parliament in a matter of days specifically to deal with this situation, deprived the prisoners of all contact with each other as well as with the outside world. All visits, including those of lawyers and family members, were forbidden. The prisoners were also denied all access to mail, newspapers, magazines, television and radio.

In short, those subjected to this law were placed in 100% individual isolation.

On September 9, Agence France Presse’s Bonn office received the first ultimatum from the commando holding Schleyer, setting a 1:00pm deadline for the release of the prisoners. The state countered with a proposal that Denis Payot, a well-known human rights lawyer based in Geneva, act as a negotiator. Secret negotiations began the same day.

On September 22, RAF member Knut Folkerts was arrested in Utrecht after a shoot-out which left one Dutch policeman dead and two more injured. He would eventually be convicted of Buback’s murder (5) . A woman, identified as RAF member Brigitte Mohnhapt, managed to get away. The search for Schleyer was extended to Holland, but to no avail.

On September 30, defense attorney Ardnt Müller was arrested. Accused of having worked with his colleagues Armin Newerla and Klaus Croissant to recruit for the RAF, he was imprisoned under Kontaktsperre conditions. The arrest was buttressed by the claim that on September 2 Müller had used Newerla’s car, in which an incriminating map had allegedly been found. The next day Croissant, who had fled to France earlier that year, would be arrested in Paris.

On October 7, the thirty-second day of the kidnapping, newspapers in France and Germany received a letter from Schleyer, accompanied by a photo, decrying the “indecisiveness” of the authorities.

On October 13, with negotiations deadlocked, a Palestinian commando intervened in solidarity with the RAF, putting the already intense confrontation on an entirely different level.

The four-person Commando Martyr Halimeh, led by Zohair Youssef Akache of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, hijacked a Lufthansa airliner traveling from Majorca, Spain to Frankfurt in West Germany – ninety people on board were taken hostage.

The airliner was first diverted to Rome to refuel and to issue the commando’s demands. These were the release of the eleven RAF prisoners and two Palestinians being held in Turkey, Mahdi Muhammed and Hussein Muhammed al Rashid, who were serving life terms for a shootout at Istanbul airport in 1976 in which four people were killed.

The plane flew to Cyprus and from there to the Gulf where it landed first in Bahrain and then in Dubai.

It was now the morning of October 14. Denis Payot announced receipt of a communiqué setting a deadline of 8:00am on October 16 for all the demands to be met “if a bloodbath was to be avoided.” The communiqué, signed by both the Commando Martyr Halimeh and the Siegfried Hausner Commando, was accompanied by a videotape of Schleyer.

Later that day the West German government released a statement specifying that they intended to do everything possible to find “a reasonable and humanitarian solution” so as to save the lives of the hostages. That evening the Minister in Charge of Special Affairs, Hans Jürgen Wischnewski, left Bonn for Dubai.

On October 15, Payot announced that he had an “extremely important and urgent” message for the Siegfried Hausner Commando from the federal government in Bonn. Wischnewski, on the site in Dubai, promised that there would be no military intervention. That evening the West German media broke its self-imposed silence (which had been requested by the state) for the first time since the kidnapping, showing a thirty-second clip from the Schleyer video received the day before.

As another day drew to an end, the West German government announced that Somalia, South Yemen and Vietnam had all refused to accept the RAF prisoners or the two Palestinians held in Turkey.

At eight o’clock in the morning on October 16, the forty-first day since the kidnapping of Schleyer, the deadline established in the October 14 ultimatum passed. In Geneva, Payot once again announced that he had received an “extremely important and urgent” message from Bonn. At 10:43am, the Turkish Minister of Finance and Defense declared that the Turkish government was prepared to release the two Palestinians should the West German government request it.

At 11:21am, the hijacked airliner left Dubai.

At noon, a second ultimatum passed.

At 3:20am on October 17, the hijacked airliner landed in Mogadishu, Somalia. The dead body of Flight Captain Jürgen Schumann, who had apparently sent out coded messages about the situation on board, was pushed out the door.

As the sun was rising the hijackers extended their deadline once again, to 2:00pm.

At 2:00pm yet another deadline past. Minutes earlier a plane carrying Wischnewski and the GSG-9, a West German anti-terrorist commando, had landed in Mogidishu.

At the same time in Germany Schleyer’s family released a statement announcing their willingness to negotiate with the kidnappers.

That night, as the double-standoff continued, the government issued a statement that the “terrorists” had no option but to surrender. Less than an hour later, the West German government requested an international news blackout of developments at the airport in Mogidishu.

At 11:00pm on October 17, sixty members of the GSG-9 attacked the airliner; guerilla fighters Zohair Youssef Akache, Hind Alameh and Nabil Harb were killed, and Souhaila Andrawes was gravely wounded. All hostages were rescued unharmed, with the exception of one man who suffered a heart attack.

The next morning, at 7am on October 18, a government spokesperson publicly announced the resolution of the hijacking.

An hour later, another spokesperson announced the “suicides” of Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader and the “attempted suicides” of Jan-Carl Raspe and Irmgard Möller. Raspe subsequently died of his wounds. (As we will see tomorrow, there is an abundance of evidence indicating that the prisoners were murdered.)

On October 19, police discovered Schleyer’s body in the trunk of a car in the French border town of Mulhouse.

After forty-three days, the most intense clash between the anti-imperialist guerillas and the West German state had come to its bloody conclusion, sending shock waves through every sector of West German society.

The German Autumn effected the entire West German left, as the State responded to the 77 offensive with a wave of repression against the entire revolutionary movement.

On April 25, just a few weeks after the RAF had killed Siegfried Buback, a student newspaper had published an essay entitled Buback Obituary, in which the anonymous author admitted his “secret joy” at the Federal Prosecutor’s assassination. While the Buback Obituary was obviously hostile to the RAF’s politics, the State seized upon the opportunity to clamp down on the radical left and sympathetic academics.

At the same time, the plethora of Maoist parties and pre-party formations (the so-called “K-Groups”) had also entered the State’s sights. After Schleyer was seized, the State moved to ban the three largest Maoist parties, the KBW, the KPD and the KPD/ML, with ludicrous claims that they had some connection to “terrorism”. All three organizations called for a joint demonstration in Bonn on October 8, 1977, under the slogan “Marxism-Leninism Cannot Be Outlawed!” Twenty thousand people marched under red flags in what would be the only joint activity these sectarian organizations would mount during the decade.

While most of these Maoist K-groups would implode within a few years, losing many members to the new Green Party, some other militants managed break through the impasse of 77 in their own way, by organizing a radical left countercultural happening, Tunix (6) , held in January 1978 in West Berlin. As the organizers (“Quinn the Eskimo”, “Frankie Lee” and “Judas Priest”) explained in their call out, “When our identity is under attack, like during the situation in the fall of ‘77, then we need to take the initiative and state openly what it is we want. Political taboos and appeals to the constitution won’t save us.”

The Tunix conference represented a breakthrough for the anti-authoritarian “sponti” scene, with as many as twenty thousand people attending. Participants took to the streets, and the first violent demonstration in a long time was held in Berlin as people threw bricks and paint filled eggs at the courthouse, the America House and the women’s prison. Banners read “Free the prisoners!”, “Out With the Filth” and “Stammheim is Everywhere.”

Nevertheless, this was a time of defeat and demoralization. As a later writer would note:

“While some people sought to criticize the state’s violence (for example, 177 professors issued a statement), most people were simply left speechless by the events… whole streets were lined with cops with machineguns, known left-wing radicals were stopped and searched, and radical left meeting places were raided.

“The ‘German Autumn’ forced the undogmatic radical left scene to re-orient itself away from factory struggles and squatting efforts and towards the growing anti-nuclear actions… In the context of the anti-imperialist attacks and hijackings by the RAF (and some barely identifiable Arab forces) during the ‘77-Offensive, the process of the splitting off of the radical left scene, which began in 1972, was complete. Increased state repression, coupled with denunciations and distancing by left-liberals and academics from the ’68-generation, made the whole affair a traumatic experience for the radical left.

“During this phase of isolation and disorientation, many comrades lapsed into resignation or joined up with the alternative movement. Another wing ‘hibernated’ in the anti-nuclear movement for a while.”(7)

As the RAF would later acknowledge: “We committed errors in 77 and the offensive was turned into our most serious setback.”(8)

It would take some time for the guerrilla to formulate the lessons to be drawn from this unprecedented setback, to regroup and to plan its next moves.

You can read the RAF’s communiques regarding this actions here:

- Schleyer Communiques

- Operation Kofr Kaddum from SAWIO Commando (October 13th 1977)

- Ultimatum from SAWIO Commando (October 13th 1977)

- Final Communique Regarding Schleyer from the Siegfried Hausner Commando (October 13th 1977)

Footnotes

(1) The Social Democratic Party of Germany, then the ruling party.

(2) Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany’s official name

(3) The Resistance, The Guerilla and the Anti-Imperialist Front, May 1982

(4) Ibid.

(5) Earlier this year former RAF members Peter-Jürgen Boock and Silke Maier-Witt stepped forward to claim that Folkerts could not possibly have been the shooter as he had been in Amsterdam that day. The two went on to point the finger at another RAF member, Stefan Wisniewski, as the shooter, naming Günter Sonnenberg as the driver of the motorcycle from which the fatal shots were fired. Furthermore, Maier-Witt claims to have informed the police in 1990 that Folkerts was in Amsterdam on the day of the shooting. It is also alleged that former RAF member Verena Becker informed the police that Wisniewski was the shooter as early as 1982. These developments have forced to German police to reopen the Buback case, and it is not outside of the realm of reason that former RAF members already released might find themselves facing a new trial when the renewed investigation is completed.

(6) A play on words which means “do nothing.”

(7) Fire and Flames: A History of the German Autonomist Movement by Geronimo, unpublished translation by Arm The Spirit. (available in German for free download here)

(8) The Guerilla, the Resistance and the Anti-Imperialist Front op cit.